With a lineage tracing back to the 1890s, Maxham Violins continues through Richard Maxham, the fifth generation in his family to carry on the legacy of making their instruments. Richard has spent his life with the violin, playing at the age of three and performing extensively as a soloist, chamber musician, and orchestral violinist. After inheriting his grandfather’s tools, wood, patterns, and violin book library, he began the lifelong process of studying all aspects of the violin. He is currently apprenticing under Daniel Smith from Lynchburg, a master wood maker and violin maker, through the 2022-2023 Virginia Folklife Apprenticeship Class. In this episode of Folklife Fieldnotes, we travel to both Richard's and Daniel’s violin making shops to meet both men and to hear about Richard’s family legacy of making violins.

Pat Jarrett: Have you ever wondered what the difference is between a fiddle and a violin?

Chris Boros: Yes, I have actually.

PJ: Let's talk about that today because I've spent some time with Daniel Smith down in Lynchburg and his apprentice Richard Maxham in his studio in Alexandria, which is quite a different shop than his mentor's shop in Lynchburg. You can imagine in Lynchburg, Danny's got this kind of wood shop. He's a woodworker. He's a first-generation violin maker and it's kind of expansive. He's got projects in the works. He's got workbenches full of old tools from past teachers. And Richard, nothing in Alexandria is that sprawling unless it’s part of the US government. So he lives in a tiny little town house and he's got one of the bedrooms that he's converted to a workshop. And there he continues the craft of five generations of his family making violins. So he's a fifth generation violin maker. Maxham Violins go back that far. And of course, I asked the most important question: what's the difference between a fiddle and a violin?

Richard Maxham: Realistically, it’s something that comes down more to playing style. The instrument itself is the same and the joke is that a violin has strings and a fiddle has “strangs.”

PJ: It's kind of silly, but Richard is kind of a soft-spoken individual. He definitely has reverence for the instruments and for his family's craft. He was brought up in Connecticut and in Iowa and his family's been doing this for like five generations here in the United States. And so these are violins, these are beautiful instruments. He was playing one of his violins in Danny's shop when we visited.

CB: Sounds like a violin to me – the way he's playing it.

PJ: Yeah, it sounds exactly like a violin.

CB: Isn't that interesting though, the same instrument and the different techniques of playing it, you get a completely different vibe.

PJ: Oh sure. For all the fiddler's I’ve seen and violin players, it's all about the technique. The bow technique; how they draw the bow across the strings; how they let it resonate. It also comes down to intent. Are you playing as a performance? Are you playing as a social gathering? It's all sorts of things. So many factors go into what makes a sound and the tools are just one part of it.

Richard: As far as my history with the violin, it's something that's just always been kind of in the blood. I'm the fifth generation in the family to be involved with the violin in some way. There's always been somebody in each generation that has played the violin or made them. When I was growing up, my father was a violin music critic, he would review recordings of classical performances and so there'd always be music playing in the background. My father also performed regularly and played in orchestras and would play in the community as well. So I'd always hear him playing and he played for me when I was really little. And when I was three, I got my first violin. And that was how I got started playing and then for the next 20 years my father taught me. We went through starting with a lot of the great classic violin methods. So that was my classical side of playing the violin. I also was involved in folk music or in old-time to some extent. When we lived in Iowa, my parents both participated in a group called The Onion Creek Cloggers that would put on dances regularly throughout all of Iowa really. I even got to play with them a couple times before we moved. But I grew up always going to the rehearsals because they rehearse once a week and I’d always come along for that.

Richard: When I finished college, I decided to apply to the Chicago School of Violin Making. During the summer time after finishing college, before I would have started at Chicago, I thought that it would give me an advantage starting there if I spent some of the time in the summer just trying to get some extra wood working skill. So I thought, well, if I could just get some basic tool proficiency before I start, that would be great. So, I started looking around to see if I could find maybe a woodworkers club or something like that, where they could just hand me a few chisels or gouges and I could just make some shavings. In that process, I was looking online one day and I happened to find on Johnson string instruments website, there was a violin made by Daniel Smith of Lynchburg. And I was just really taken aback because this violin was stunningly beautiful. At that time, phone books were still used, and so I was able to look Danny up in the phone book, he was listed, and so I gave him a call and I told him that I was looking for some introduction to just using the hand tools. So he said, why don’t you come to my house and we can talk a little bit. So I came over and we talked for probably a couple hours but we just hit it off immediately. At the end of the conversation, Danny said, well I think what you ought to do is just come make a violin with me. It felt so perfect. I was so impressed with his work. When I came over to his house he showed me some of his violins. I had gotten to play them. So having an offer to work at the bench with him was just a dream come true. I'd never even expected that something like that would be offered.

PJ: I think their apprenticeship is really beautiful because Danny is kind of a good old boy down there in Lynchburg. He used to be a firefighter and was a bodybuilder.

Daniel Smith: While I was in the fire department, I used to do a lot of repair work for players in the area. Then I decided I wanted to build and then met Russell Barfoot through another fellow named Donald Watts, he introduced me to Russel. Donald had built some instruments. He had Dolly Parton and Porter Wagoner pulled their bus on his land in Monroe, Virginia, and out of that bus that would go in the surrounding areas and do gigs. Well anyway, he built a guitar for Dolly and I saw on TV playing that guitar one time, so went to see Russell and we clicked instantly. So we built about 15 instruments. He got this cancer and he didn't last long with it. So I carry on the legend of building violins. I've built 75. I'm working on my second cello. I’ve repaired hundreds of instruments. It's been a passion of mine ever since I got out of the Army - being interested in violins. The more you see, the more you learn and when I started having violins to work on, they pretty much looked the same to me. And some of the ones that were cheap I thought were expensive and vice versa, but it starts to come together. You can hold a violin on the other side of the room, and I can tell you right now if it’s worth looking at again. It just happens, like a child learning to talk, it all of a sudden it just happens. And you never stop learning that; the more you see, the more you learn. And Rich has become the teacher and me the student with seeing these famous instruments. Some of them I'm impressed with - always impressed with the prices they bring - but not with the workmanship.

PJ: I'm interested to see Daniel’s influence on Richard and to see their relationship really flourish. It's been a pleasure to watch so far.

Daniel: If you do something with your hands and your mind together, it's a good antidote for the misery of the world, you get lost and what you do and my wife also has a wonderful hobby. She knits these sweaters for the needy and she's done up to 100 a year. Her name is Phyllis. So she’ll sit and knit and I’ll sit and carve.

CB: Do you think there are any classical violin players that would ever say they play the fiddle?

PJ: It's funny you ask that because years ago I was in Staunton at Marino’s Lunch and I recognized a violin player from the Staunton Music Festival who came in to the Tuesday night jam at Marino’s. And I said, what are you doing here? And she said, oh every time we have the music festival I come in here, it's just such great improvisational music and I love how it feels. It's such a difference from what I do on stage at the Staunton music festival which is a classical music festival; a very popular one in Staunton. I joked that she walked in with a violin walked out with a fiddle. This is one of those areas that I really like to dive into and scratch because there's a deep vein of what makes music, what makes expression, and what tools have to do with it. I've always thought that tools are a means to an end, you can use a hammer and build all sorts of things. I feel like instruments are the same way. This is a tool. They have to be well made, they have to be a certain quality, but from there it's open range. You can go wherever you want with it. As soon as I walked in [the shop], he was listening to a fiddle record. It's just me and him in his workshop - you can hear he's working on some edge work on one of these violins and listening to a fiddle record. He fits in. At the Richmond Folk Festival this year, we had a luthiers tent where we had all different makers under one tent and Richard and Daniel were both there and later that day when we were there at Richmond, they all took the stage and they played a song together. They played Lee Highway Blues. Under the luthier’s tent in Richmond, we had KT Van Dyke, Mac Traynham, Dr. Deena Jennings, Lisa Ring and her husband Bill, Michael Brewer, Spencer Strickland, Karlie Keepfer and Sophia Burnett and their mentor Chris Testerman, who learned from the late great Albert Hash.

CB: When you're at Richmond and you have these luthiers together, is there competition?

PJ: It’s not really competition, it’s way more camaraderie. These guys like talking about gear and they're like talking about their craft. They like talking about wood quite a bit. It's one of their favorite pastimes and actually Richard I talked about that - he was talking about this piece of wood that his great grandfather made a bunch of violins out of.

Richard: This is a violin that my great-great-grandfather Otis H. Maxham made in 1916 in Erie, Pennsylvania. And the back on this one is kind of his characteristic wood. He bought a whole tree I think, a great big log of this beautiful old maple and made the majority of his violins with that particular wood. I've seen probably about 20 or so of them. And a lot of them have this wood. It's just this beautiful deep curl in it. The one that I played with when I was growing up had the same wood with it and we ended up finding the twin of that violin too.

CB: He said 1916?

PJ: He said 1916.

CB: Great-grandfather? Or great-great?

PJ: Great-great grandfather.

CB: And so there are three more before that? Great-great-great-great? Or is there one more great?

PJ: Well it’s him. His father. His grandfather. His great-great, which would be Otis, and one more beyond that. Great-great-great.

CB: Wow. And who made the 1916?

PJ: Otis Maxham.

CB: So it even goes before that.

PJ: Yeah, they're ones made before that. It's amazing to think about it. But sure enough I've seen 100 year old instruments played by amazing musicians. And basically every luthier I've talked to has said that the wood makes all the difference. But the thing is, Richard has all these stories about his own violins. And so he talked about this violin that he is great-great grandfather made in 1916 that he played as a kid and this violin his father played, his grandfather played, this is one of these well-loved instruments that was taken on trips, that was played out. It's been broken and repaired a bunch of times. It has miles on it, but he still loves it. And he takes care of it. But the interesting thing is, you remember how he said there's a twin to this one? Well he said recently that they found the twin.

Richard: So I had that violin and played it for years. We had heard that my great-great-grandfather often made violins in pairs. But we've never come across a second violin made at the same time. And then a friend of the family got in touch and said that he'd come across a listing for a Maxham violin. It belonged to somebody who lived in an Amish community and it had been there maybe most of his life. We bought it sight unseen just knowing what it was, but we didn’t know was it was going to be exactly or when it was made. And then we got it and opened it and looked at the label and it was the same year as that other violin – it was the twin, same wood and everything, but that one was pristine. Of all the Maxham violins, that one was probably the most pristine so you could see just what it looked like when it came off of the workbench. We always kept the two in a double case it was nice to reunite the twins and have them back together again.

CB: Wow, what a find.

PJ: Yeah, Richard has stories about these violins. There was one violin that was found in a home renovation. They removed a panel on a basement wall and there's a violin case back there. It's wild and it's amazing that there's all this history just in one family. And what a blessing to be able to make these instruments and have such a legacy fully intact.

CB: It must be special for him to hold this violin that his great-great-grandfather made. Here it is. He's still holding it.

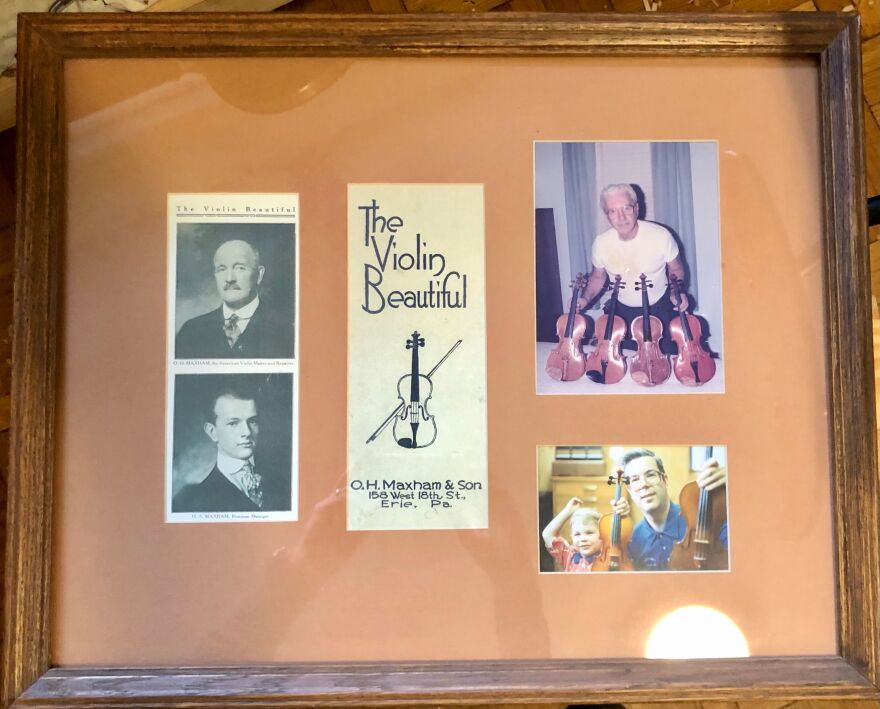

PJ: It's so cool. And he's got a photo of his great-great grandfather on his wall. It's one of those old-timey portraits and there's reverence for the family legacy here. I can't even imagine. For example, today, this is a shirt that I got out of my grandfather's closet, right? And I feel like this is touching time when I'm wearing this and I wear it all the time. And when I'm wearing it out, it's not an heirloom. But I can't imagine holding something that my great-great grandfather made by hand.

CB: And it still sounds so good too.

PJ: Right?

CB: Beautiful. It's interesting to me that they have a story for each one. These really aren't just instruments to Richard. These are personal things that he has made and he's put his love into. To name them? That just goes to show you how much he puts into this.

PJ: Here's the thing too, Chris, I don't think Richard is alone in this and furthermore violins are made in all types of places and all types of situations. And currently, Richard is working with some violin makers in the Ukraine who are still making instruments even though their shops are being threatened by shelling. He's doing his best to sell these violins and to get them out in the world because it's really tricky to get violins out of a war zone. He talks about this.

Richard: I got an email from the violin maker in Ukraine. So, there's a guy that plays in the opera here. And he is Ukrainian himself. And he sells violins made by this family. And I advertised on this website that I had one of them that I got through him. And this other guy saw that and got in touch with me. He sent me a violin. And I was just blown away by it when I got it. I didn’t really know who he was so as I started to talk to him more I was really impressed. I sold the first one to a friend of mine. Also, the war in Ukraine started as he was trying to finish that violin. He had gotten about three-quarters of the way through. And he had to move and everything and then they started shelling by his house. The family had to get out just to be safe. He finally got that violin done and he sent it to me. That one sold in a day. I’m doing everything that I can to try to promote him as a maker because I think he does fantastic work.

PJ: It shows the heart and the camaraderie of this community of makers that in the worst of times not only are they still making but they're still finding fellowship and resources within this community. I think it's really amazing that Richard is helping out and bringing attention to these makers and trying to boost them up in their time of need.

CB: So, Richard is selling these violins from Ukraine, a completely different violin maker, he's selling them for him?

PJ: Yeah, he is.

CB: This is like Martin guitar selling a Taylor. It goes to show you this really is a community of people.

PJ: And also extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures and at some point the community is stronger if there is representation and if a violin maker can continue to make work, even in a war zone, pretty amazing. Andrash Taras makes these violins and Richard is doing all he can to promote him. The stories of these violins, I think it might affect me more than the family connection, the Maxham generational story is so beautiful and that he's learning from Daniel Smith, who is an accomplished woodworker and who is an accomplished maker, also brings me joy, but this story from Ukraine of these violins really makes me think. I can't imagine trying to do my job while shells are dropping outside.

CB: Especially a job like making violins because you don't think in a war zone that would even be still be happening.

PJ: It's one of those things. Like is this actually necessary? Are these instruments necessary? And I think resoundingly, yes they are.

CB: Yes. Absolutely

PJ: Because what else is there if not the human expression and the ability to communicate through music and communicate with your communities?

CB: It has to continue, no the matter what's going on. The music's got to keep going, Pat.

PJ: Humans are stubborn like that, aren't they? The Maxham violin line is in good hands with Richard and I'm really excited to see what he and Danny do together in their apprentice in the Folklife Program. And they really work well together.