There is a wealth of information about Virginia's climate and how it’s been changing over time. But the state is not a monolith.

“We’ve got everything from the coastal Tidewater region all the way to the mountains, and those are incredibly different environments,” said Luis Ortiz, an assistant professor of climate applications at George Mason University.

A new report from scientists across the state pulls together pretty much everything officials know about climate impacts, including those regional differences.

“There is enough variability in the geography of Virginia and the populations that we thought we really needed to provide a more detailed view of how climate is changing here,” Ortiz said.

The first Virginia Climate Assessment was released Wednesday, spearheaded by GMU’s Virginia Climate Center, which launched in 2022. More than two dozen academics from across the state contributed, including several from Old Dominion University and William & Mary.

Ortiz, one of the lead authors who also helped coordinate the report, said it’s modeled on the National Climate Assessment, which in turn complements an international version.

The congressionally mandated national assessment, last released in 2023, includes a chapter about the Southeast region, but there’s none focused specifically on Virginia. (The Trump administration this spring disbanded authors of the next assessment and announced it’s being “re-evaluated.”)

“We were a little surprised that this document did not exist already,” Ortiz said. “I think it’s particularly important because it provides sort of a magnifying glass on the commonwealth.”

Over the past year, the collaboration dug through scientific literature and data, drawing from more than 300 sources, he said.

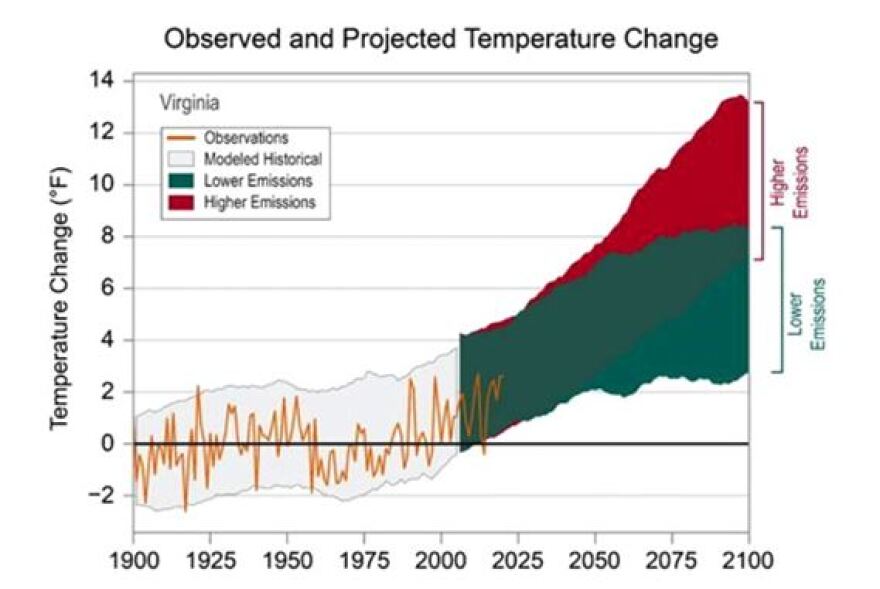

Virginia faces three primary hazards from climate change, scientists say: rising temperatures, rising tides and rising rainfall. Each has wide-ranging consequences.

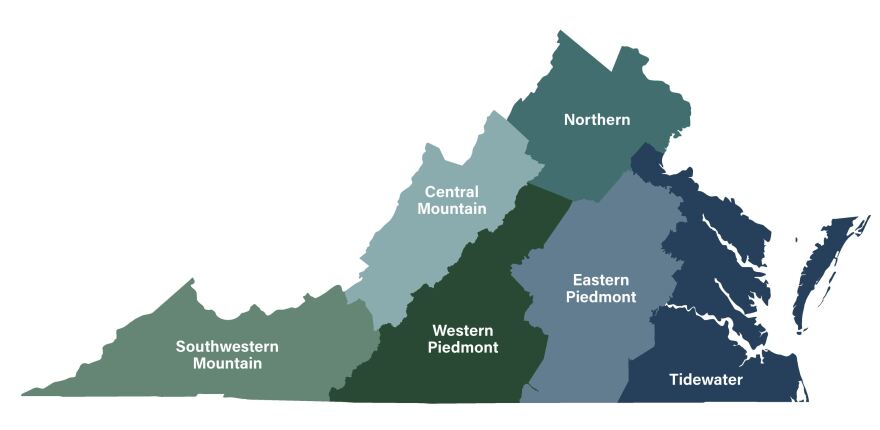

The assessment divides the state into six “climate divisions,” with Tidewater encompassing the entire coastal area.

Coastal Virginia is experiencing sea level rise faster than the global rate because the land is sinking as waters are rising.

That will lead to increasingly more frequent coastal flooding. But the report also highlights other impacts, such as saltwater intruding farther inland, contaminating water and soil.

That process “disrupts established food webs, degrades freshwater wetland habitats that serve as critical nurseries for many species and can lead to the formation of ‘ghost forests’ where salt-intolerant trees die off, ultimately transforming productive coastal ecosystems into less diverse salt marshes or open water areas,” authors write in the assessment.

Meanwhile, severe weather is becoming a more routine threat.

Though the number of rainy days has not yet changed, the total rainfall on those days continues to increase, making flash floods and standing water more likely.

“Increasing variability in rainfall may require costly public investments and result in the loss of property as river-based water storage needs to be augmented with new reservoirs,” the report states.

On the flip side, sudden short-term droughts are becoming more frequent in the drier seasons of summer and winter.

Ortiz said one of the topics he found most surprising was extreme heat.

“Typically, here in the commonwealth, the conversation on these weather-related hazards steers toward flooding, and for good reason,” he said. “But when we started looking more into the risks related to heat, it just touches on so many aspects of our infrastructure and human health.”

Heat can impact the ability of transmission lines to carry electricity, for example, and affect transportation systems such as roads and rail lines, which may require more maintenance or break down during extreme events. (Extreme heat in June, for example, forced the Great Bridge Bridge in Chesapeake to close after its metal parts expanded and malfunctioned.)

A hotter and wetter climate also makes it easier for humidity-loving species, such as ticks and mosquitoes, to spread diseases.

Some temperature-based changes may have positive side effects, such as stone crabs spreading north into the Chesapeake Bay which could provide additional revenue for crabbers, Ortiz said.

Temperature change data shows that the state’s coldest days are warming much faster than its warmest days, he said.

“We’re losing winter days much faster than gaining extremely hot days in the summer. And that has a lot of impacts on agriculture,” he said. “People usually think, ‘Oh, it’s going to get very hot in the future.’ But also it's going to get much less cold.”

The Climate Center plans to update the assessment regularly, incorporating feedback from officials and residents about what they’d like to see included.

Ortiz hopes it can serve as a jumping-off point for action, guiding decisions such as where to invest in adaptive infrastructure or plant trees.

“It’s both informing the people who spend the money to protect entire communities, but also empowering people with some of the knowledge of what has already happened,” he said. “Because the climate has changed already.”