In the winter of 1609, English colonists at Jamestown were starving.

The few hundred people living there turned to eating horses, dogs, vermin – “really anything they can get their hands on,” even resorting to cannibalism, said Leah Stricker, senior curator with Jamestown Rediscovery.

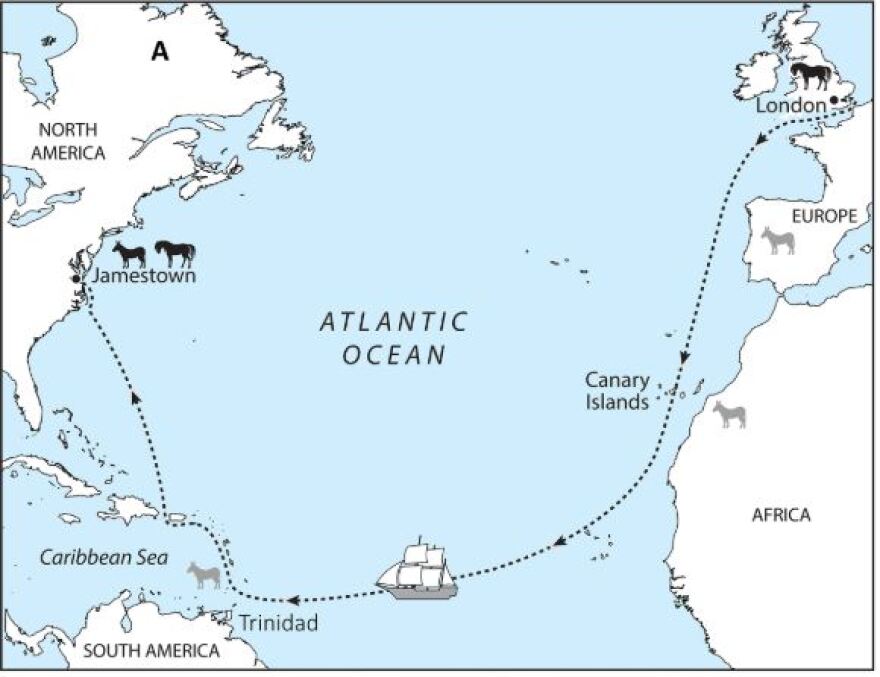

Archaeologists are now adding another animal to the list: a donkey. A team of two dozen researchers recently published a study identifying a more than 400-year-old tooth as belonging to a donkey likely taken from the tropics.

“We wouldn't have expected a donkey because it's not mentioned in the historic record,” Stricker said. “It's kind of a groundbreaking find for that reason because it is, in a way, like rewriting that historic record.”

The finding is the latest in a long-running effort to examine more than 620,000 bones that have been excavated at the historic Jamestown Fort, which was established in 1607 as the first permanent English settlement in North America.

Most of those artifacts come from the First Well, which colonists filled in shortly after the starvation winter as part of an effort to start anew and likely hide evidence of cannibalism.

The donkey tooth was part of a smaller trove of about 7,000 bones found in 2012 in an adjoining old kitchen cellar.

William Taylor, an assistant professor and curator of archaeology at the University of Colorado, helped identify the tooth, previously presumed to belong to a horse. He had long been working to explore how horses impacted societies around the globe, including Mongolia and Patagonia.

Using newer techniques such as genomic sequencing and isotope analysis, Taylor’s team more recently learned about horses in the American West.

“The spread of horses into an enormous continent like North America is a very multifaceted and complex process,” he said. “We knew that there were missing pieces of this story here, particularly the early connections between British colonists and the Eastern Seaboard.”

Taylor reached out to Stricker a couple of years ago and eventually visited Historic Jamestown to inspect its extensive collection of equine bones.

Jamestown officials already knew early colonists brought horses, based on artifact analysis and documents. They also knew many of those animals were butchered during the great starvation.

“Having fed upon horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to make shift with vermin, as dogs, cats and mice,” wrote George Percy, an early colonial governor of Virginia.

The donkey tooth stood out because it’s similar to horse teeth but smaller, Taylor said. They also examined the tooth’s specific enamel patterns.

Further analysis, including DNA, confirmed the donkey’s identity and traced its ancestry to the Caribbean or West Africa.

Researchers say colonists likely picked up the animal during a supply mission stopover shortly before the starving period. Last year, a separate team identified 400-year-old bones from an iguana, also believed to be taken from the Caribbean.

Stricker said the discovery was surprising because donkeys are traditionally associated with Spanish colonial sites.

It also gives historians additional – gruesome – insight into the winter of 1609-10.

Analysis of the horse and donkey teeth show they’d been split open to try to extract even the tiniest bits of marrow or other sources of nutrition. Bits of metal remain from where the teeth were struck with an ax.

“They really do show an extraordinary level of desperation,” Taylor said. “By the time you're down to slaughtering and eating your mode for transport, you know it must have been pretty dire circumstances.”

The tooth from the kitchen cellar is the only evidence so far of a donkey. But it’s possible there were several more at Jamestown.

In fact, writings from colonists after the starving time requested their compatriots send donkeys, implying they had already observed the species fare well in Virginia, Taylor said.

“I think this shows us that you can't take things like the few ships’ registers or simple written summaries as literal truth as to what animals were or were not making it into these transcontinental voyages,” he said. “The archeological record is always only a fraction of the true landscape of people and animals in the ancient world.”

The donkey, he said, could be an “unsung hero” of the Jamestown settlement.