In the second of a five-part series, WMRA's Randi B. Hagi speaks with two siblings who were at the forefront of school desegregation in Warren County. (Please be advised that this story recounts mentions of violence, and contains an offensive racial slur, and a mention of sexual assault.)

Back in the 50's, there was no high school for Black students in Warren County. Young teens including James M. Kilby, who is now the Reverend Kilby, were often sent out to a boarding school 60 miles away in Manassas to continue their education. He was 13 in 1955 – and said that was a rough year. He was often hungry and cold.

JAMES KILBY: I caught a cold, lost about 20 pounds … so after that year, I believe my father had made up his mind that he wasn't going to send me back to that boarding school.

The following year, he attended the Johnson-Williams School in Berryville. But after an incident where the bus ran off a snowy road, leaving Kilby, his brother John, and their classmates stranded for hours, his father had had enough of faraway schools. Besides, Kilby's younger sister Betty was about to start high school.

BETTY KILBY FISHER BALDWIN: It was my Dad's reaction to the form that caused me to say, "okay, we're doing something different."

Betty Kilby Fisher Baldwin had brought home a form one day, on which her parents were supposed to indicate which Black high school they'd send her to. Her father, James W. Kilby, wrote in "Warren County High School" – the white school. When the district refused to enroll Baldwin, her Dad consulted with NAACP attorney Oliver W. Hill, who agreed to represent their family and other Black students in the county.

Both siblings recount terrifying nights of white locals trying to intimidate them – including shooting at their house and attacking their livestock.

KILBY: I know Front Royal. I know what we had to go through. I know that they burned crosses in the yard and shot around the house and poisoned the cows and mutilated a calf.

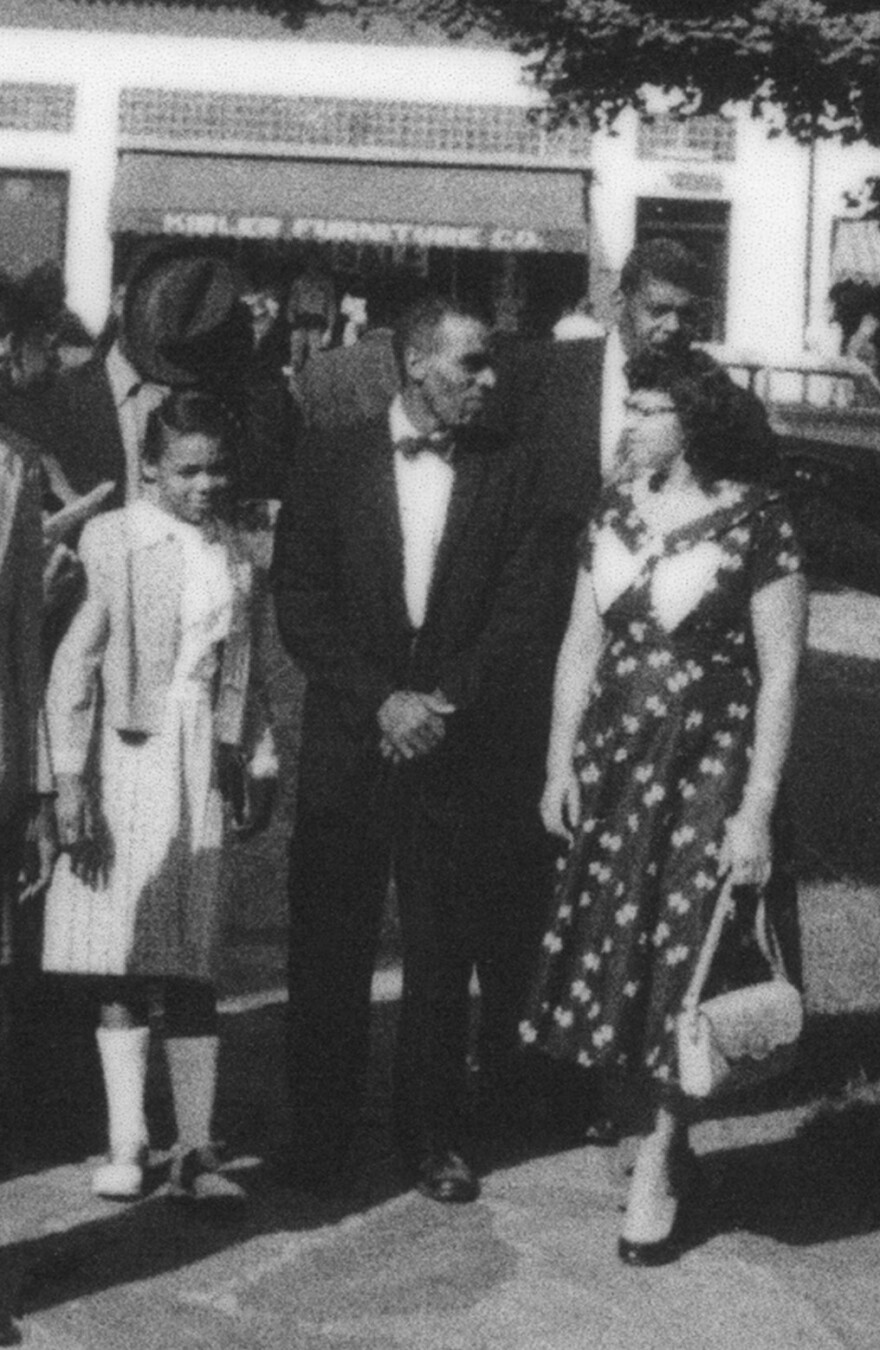

When Federal Judge John Paul ordered the Warren County School Board to admit the 23 Black students in September of 1958, Governor Almond closed the school. The Kilby kids went to school in Washington, D.C., while the legal battle raged on. After the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed Paul's integration order, they returned to Front Royal. And on February 18th, 1959, they walked past a crowd of screaming white segregationists, up the hill and into Warren County High School.

Watch a video of James M. Kilby (in glasses), followed by his sister Betty as they walk up to Warren County High School on February 18, 1959 in WSLS footage. Courtesy of The University of Virginia Library.

KILBY: That first day … [haltingly] I don't know really how to describe it, it was … you know, as a 15 year old, you wonder why… you see these signs they put up that say "n—--s go home," and "we're gonna kill you n—--s," and, you know, stuff like that coming from a grown up.

The 23 Black students were the only kids in the building that school year, as the white students stayed in private schools. Even by that fall, less than half of the white kids had returned. Kilby said that once they did, the Black students had to move in groups to avoid being harassed or threatened. He just stayed focused on his studies until he graduated in 1961 – one of the two first African American students to be handed a Warren County High School diploma.

KILBY: I don't even remember walking across the stage. I was so nervous.

After her older brothers and some of the other Black students had graduated, Baldwin said there weren't enough of them left to travel the hallways together – and that made for a very dangerous school building. Baldwin said she used to take a shortcut through the auditorium to get to class – and one day, she was caught and raped by a group of white boys.

BALDWIN: I had developed a pattern. And I paid the price for it … if there was anything that could have killed me in the movement, who would have thought that it was not a bullet, or a beating, but a rape. That almost took me out, and I couldn't eat. I couldn't sleep. And in wanting to die, I could just close my eyes and pretend that I was just going to float to heaven. And I would pass out.

She persevered, in part, for her father's sake.

BALDWIN: There were days that death would have been more humane than to have continued on this journey. But my father was determined, and there was no way in God's green Earth that my Daddy was going to stop.

Baldwin graduated in 1963. She went on to work at Rubbermaid and Atlantic Coast Airlines. She holds an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Shenandoah University, and has written two books, titled Wit, Will, & Walls, and Cousins. Kilby went into the National Guard and worked as a White House messenger. He is the former pastor of the First Baptist Church of Washington, Virginia, and has written a book titled The Forever Fight.

Throughout the siblings' lives, their father's strength and faith in God has been a guiding force.

KILBY: You know, thank God my father was brave.

BALDWIN: My Daddy said that if you were doing it for yourself you would surely fail. You would surely give up and fail. But if you're doing it for the greater good, you will succeed.