If you live in a place that's prone to massive wildfires, there's one phrase you always listen for: "the fire is (x) percent contained." A 95 percent contained fire sounds a lot less scary than a 25 percent contained fire, and if you're debating whether or not to evacuate your house, that number might make all the difference.

But containment doesn't necessarily mean a fire isn't still raging. Rather than describing how much of the fire has been put out or beaten back, containment actually refers to the perimeter that firefighters create around the fire to keep it from spreading.

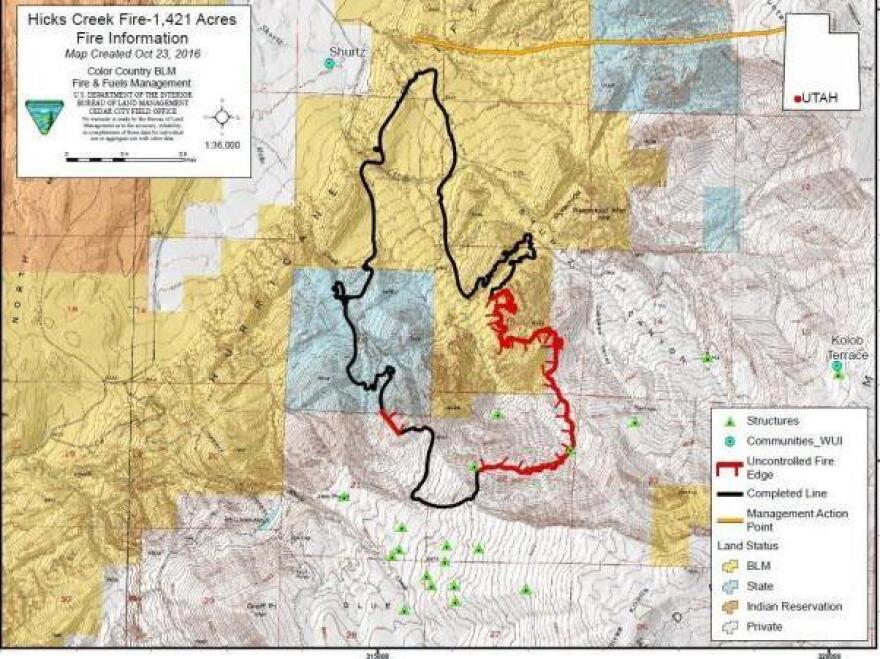

Take California's Thomas Fire, for example, which as of this writing is at 60 percent containment. That means that 60 percent of the fire is surrounded by containment lines — any physical barrier that stops the fire from passing a certain point. Those lines can be trenches, natural barriers like rivers, or even already-burned patches of land. Most often, the containment line is a shallow, 10- to 12-feet wide trench firefighters dig into the dirt.

According to NPR's Kirk Siegler,

Containment simply means that a line will have been dug all the way around the perimeter of the fire, but the blaze itself is expected to still burn within it for weeks, if not months.

If a fire is 100 percent contained, that means firefighters were able to complete a perimeter around it and stop it from spreading. It doesn't mean the fire stops burning.

That poses another problem — while it's relatively rare, fires can sometimes jump containment lines. Extreme weather conditions can push fires over containment lines, undoing firefighters' progress and putting more land at risk.

That possibility hangs over the Thomas Fire in California, which has been stoked by the Santa Ana winds. Containment levels there have already dropped once due to the winds, from 15 to 10 percent on Dec. 10.

Once a fire is contained, firefighters enter the "control" phase — the kind of thing people might typically associate with firefighting. According to Northwest Public Radio,

Controlling a fire means ensuring that the fire can't spread or cross the containment line. That means putting up barriers, removing or burning any fuel that could help the fire spread, and cooling any hot spots – those are especially active parts of the fire that could suddenly jump.

Currently, in a state that's seen the most destructive fire season on record in 2017, California's Thomas Fire is second only to the wine country fires in November. Full containment might not come until early Jan. 2018 — and even then, it won't be over yet.

Benjamin Purper is a National Desk intern.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.