The flu pandemic of 1918 lasted from January of that year till about December of 1920, and it infected roughly 500 million people. But what was life like during that time? And how did the federal government respond?

WMRA’s Chris Boros was curious about this so he spoke with Andrew Phillips, curator at the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum in Staunton. Chris asked Andrew how that pandemic started and just how bad it got.

Andrew Phillips: The 1918 Flu Pandemic seems to have arisen in the early months of 1918 but it spread pretty rapidly. It was behaving like a typical flu for its first waves and it faded away as the sort of Spring wore on, but then it came back with a vengeance. In the U.S. about 675,000 people died and about 60 million contracted it and that’s about half the population of the country had it at one point or another.

WMRA: It sounds like it was way worse that what we’re dealing with now? Is that safe to say?

AP: The very important difference I suppose, although I guess we’ll see, is that the Spanish Flu went from January, early 1918, and didn’t really end until late 1920. So, it was almost two years long and we’re only a few months into this. But, the Spanish Flu went on for a very long time.

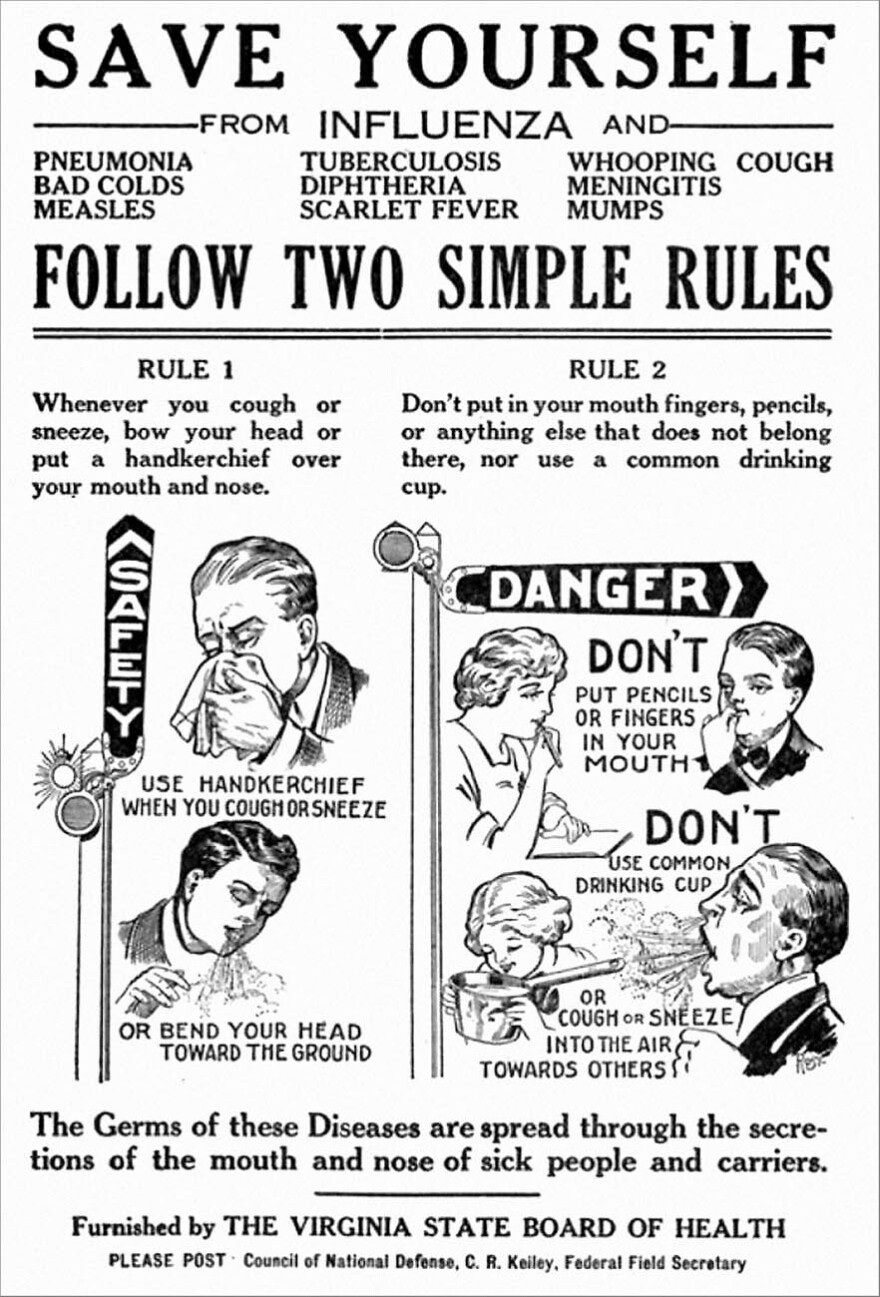

WMRA: What did authorities tell people back then? I mean was there social distancing, were people wearing masks? How similar was it as to what we are experiencing now?

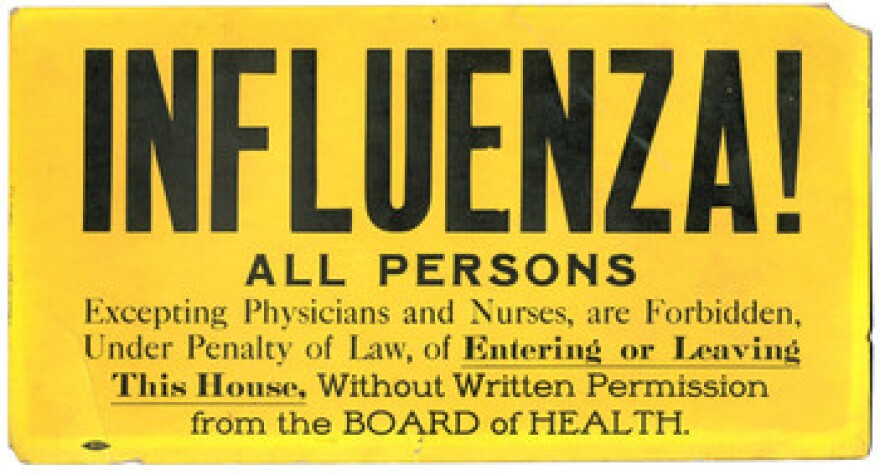

AP: There were a lot of similar recommendations made. Social distancing, although they wouldn’t have called it that, they talked about encouraging people to stay indoors, don’t shake hands, wash your hands, wear masks. Schools and theatres, public places were closed, restaurants and bars, but masks were a big part of it. How effective they were is an open question or some even said you shouldn’t be outside without a mask on.

WMRA: How did the pandemic effect our region specifically? How many deaths were there here and what was life like for people living in the Valley during this time?

AP: It’s hard to pinpoint so much because we were, and still are, fairly rural. We have a lot of data, a lot of information, about when it came to Virginia. It seemed to come through the ports of Newport News and Norfolk and spread from there. By the end of the pandemic, it’s believed that some 300,000 Virginians caught the disease, based only on death certificates. The number who died is a little under 16,000 but that doesn’t really help in more rural areas like the Shenandoah Valley, where so many people were sick and couldn’t go into the hospital, or perhaps didn’t get the sort of death certificate, their families tried to take care of them and they passed away at home. So, the numbers for those who contracted the disease and those who died from it, are almost certainly much higher.

WMRA: You lecture on this for The Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum in Staunton and Woodrow Wilson was the President during the Pandemic, so how did he respond? What did he tell the American people during this time?

AP: He does not respond, he didn’t tell the public anything. Unlike today, there was no daily Presidential briefings, at no point did the White House issue a statement about the Pandemic. This is a time when the federal government had a very different role in everyday people’s lives.

WMRA: Do you think he didn’t think it was that big of a deal or do you think that he just had so much on his plate with the war, that he couldn’t deal with the Pandemic on top of it?

AP: The war was his primary focus. So, by the time the flu comes around, we are still very much trying to raise up what will ultimately be many millions of men, to be shipped overseas to participate in this fighting.

WMRA: If there’s one thing we can learn from the Pandemic of 1918 in compared to what we’re dealing with now, what do you think it would be?

AP: I think what one of the most important lessons is speed. Philadelphia was the hardest hit large U.S. city, partly because they waited two weeks after the disease showed up in the area. St. Louis, Missouri is a great counter example, the first cases showed up in the St. Louis area and within two days they instituted what we would now call, enforcing social distancing. They ended up with a mortality rate less than an eighth of Philadelphia’s, and it was because they moved quickly, it was because they saw what was going on in other parts of the country and as soon as it showed up in St. Louis, they said we’re shutting this down. It doesn’t free them from the Spanish Flu, it still circulates in the city, but the death rate is so much lower than areas that didn’t act this quickly.